snippets #13 - 1.8

On evaluating startup metrics

A first-time founder sent me an email today asking “what north star metric(s) did you use to raise your seed round? Was revenue more important, or user engagement?” It’s probably the thing founders ask the most, so I’m digging in to startup metrics in this post!

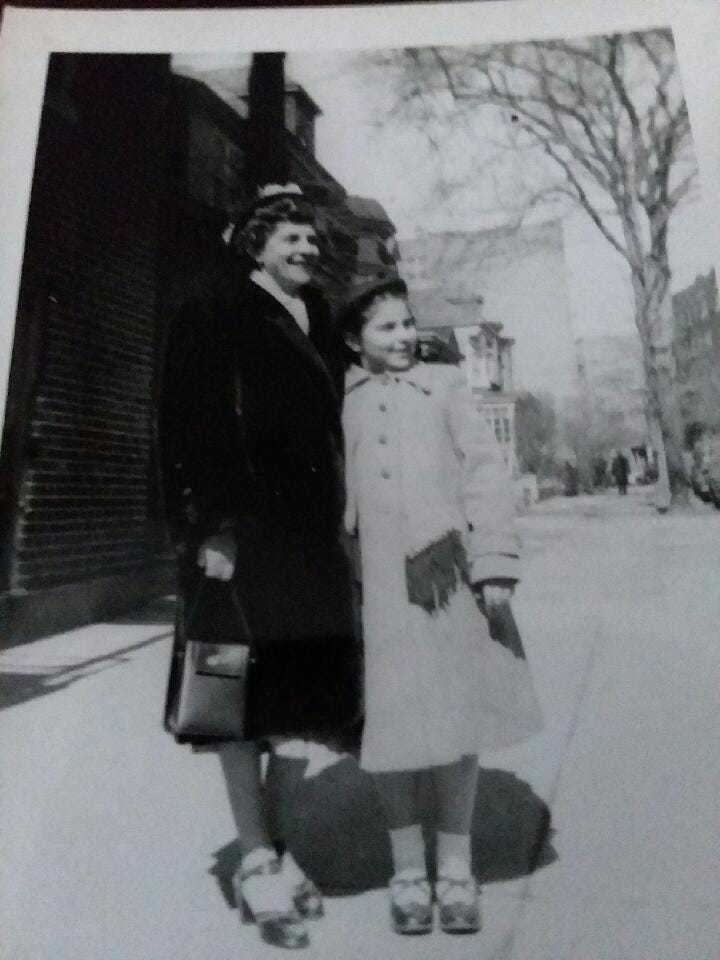

Evaluating startups is all about risk. I often use an analogy of coins on a table to walk though how investors think about evaluating this risk. (Side cute story about my great grandmother and coins. She wanted a fur coat from Macy’s and saved up her dimes to buy it herself. It was a $300 coat. That’s a lot of dimes! The picture below is of her in the coat.)

Let’s imagine my great grandmother’s 3,000 dimes are on a table. Each of those dimes represents something risky about your business. “Will the product work?” “Can the company hire?” “Can the company build what they say they will?” “Is the market big enough?” This list goes on and on.

Every time you present to investors, your job is to try to take some of those dimes off the table. The table will never be empty. If it was, you likely wouldn’t be looking for investment. It’s not about clearing the table completely, it’s about making the bet better.

What does this have to do with metrics? Metrics are the most powerful tool you have to tell your story and to take the dimes off the table. If used correctly.

There are a number of data points all investors look for (especially in the early stages). I’ve posted about some of them (team, market size, etc.) in an earlier post here. This post focuses instead on some examples of how operational metrics can be your best asset (or worst).

(Note: these are all completely made up examples.)

Company A : Marketplace with hardware component

Company A offers a sensor for corporate offices. The sensor sits on a shelf under paper goods (paper towels, printer paper, etc.). It then alerts the office manager when it’s time to re-order goods. The sensor is a trojan horse for a digital office supply marketplace.

What if they presented the slide below?

This looks like growth is relatively slow, they’re not adding too many customers, revenue is negligible, and they provided a margin on hardware which is irrelevant (it’s the marketplace that matters). This doesn’t tell a strong story.

What if instead they focused on usage? They told us that when they sign a new office up, 90% of their paper products are tracked. And that amounted to over 2,000 different items per company. Monthly, even with their small customer base, they’re pushing 120 alerts to companies letting them know they’re running low.

This company is trying to convince us that they can get companies to buy from their marketplace - that there are enough products and that companies need a solution like this. In the first slide, I see the company isn’t doing that great and they’re focused on monetizing hardware when the marketplace transactions are what really matter. The second slide starts to tell the story that there’s a real market interest, that the company can dominate in one product category right away, and that there is enough frequency that a marketplace could make sense.

Company B: IP heavy

Company B is building robots that fully design and build homes faster and more affordably. This is a long term, truly transformational play and requires a lot of capital up front for engineering. There is a lot of unique IP and the company is going to be focused on scaling in the market in 5-7 years as the first player in the space. As part of their development timeline, they work with a few big construction firms to beta test and to build out a unique and proprietary dataset.

Below is the slide they present to us.

Similar to the challenge above, the company is focused on the wrong narrative. This gets us thinking about revenue growth rather than technology development. What I want to know when you have a long development process and unique IP is: where are you on your development timeframe, is the technology truly differentiated, how do you deploy, are you thinking about commercialization, and what’s the plan for commercialization? This slide instead tells me you’ve worked with 2 big enterprise firms, deployed what seems like a lot of robots (though we have no context) and yet, you’ve done barely any revenue. How can we make the jump to these big revenue forecasts if 2 of the top 10 firms amounted to very little revenue?

Instead, you could focus on metrics like actions completed or beta devices deployed and show me how big the opportunities really are for those projects. Below, I showed an example of both robots deployed and actions completed, but you could probably get away with just robots deployed and deploy potential. This shows me you know how to deploy, there’s a lot of potential, and you know that your north star metric is robots deployed. Now, I really only need to believe that the technology is differentiated and that you have a big enough pipeline of big firms to get to.

Get to YOUR north star

There are so many metrics you can use to describe your business. The best advice I can give is to try and identify the 1-3 things that determine ultimate success for your business. In the construction example above, if that company can deploy robots quickly, they win. So they need to get big firms on board and deploy quickly across their sites. In the marketplace example above, alerts will ultimately make them money, and number of items determines how big it can really get. For most SaaS companies, you’ll want to look at revenue metrics once you’re generating revenue (LTV, CAC, CAC:LTV ratio).

Remember, metrics mean different things to different businesses. Ever heard of Joseph Brenninkmeijer or C&A stores? He reevaluated how margins could work. He decided to cut margin (discount store) and focus on driving up profit from a bigger volume of sales. He’s one of the first discounters. For most people, bigger margin is better, but for C&A, volume of sales was the metric that mattered.

Once you determine your north star metrics, make that the focal point of your story. Ignore the vanity metrics (metrics that don’t mean anything, like system logins in most cases) and leave all the other fluff out.

Hope this is helpful!

Some additional metrics resources:

https://a16z.com/2015/08/21/16-metrics/

https://neilpatel.com/blog/9-metrics/

https://medium.com/swlh/startup-metrics-370a07de9ff7

https://startupdevkit.com/types-of-startup-kpis-metrics-to-measure-with-examples/

What I’m reading

One of my absolute favorite people started a substack and his first post is awesome! He’s an expert in all things safety (built and sold a company and now leads safety and risk at Lyft) and always has a great perspective on live/work/entrepreneurship. Check out his first post of work life harmony here.